The Garinagu are a unique fusion of the Carib (Kalinagu), Arawak (Lokono) and African people, who were birthed in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. In 1802, they arrived and soon settled on Belizean shores, as celebrated with the national holiday Garifuna Settlement Day. Hopkins Village is one of the most authentic living examples of the Garifuna culture in Belize.

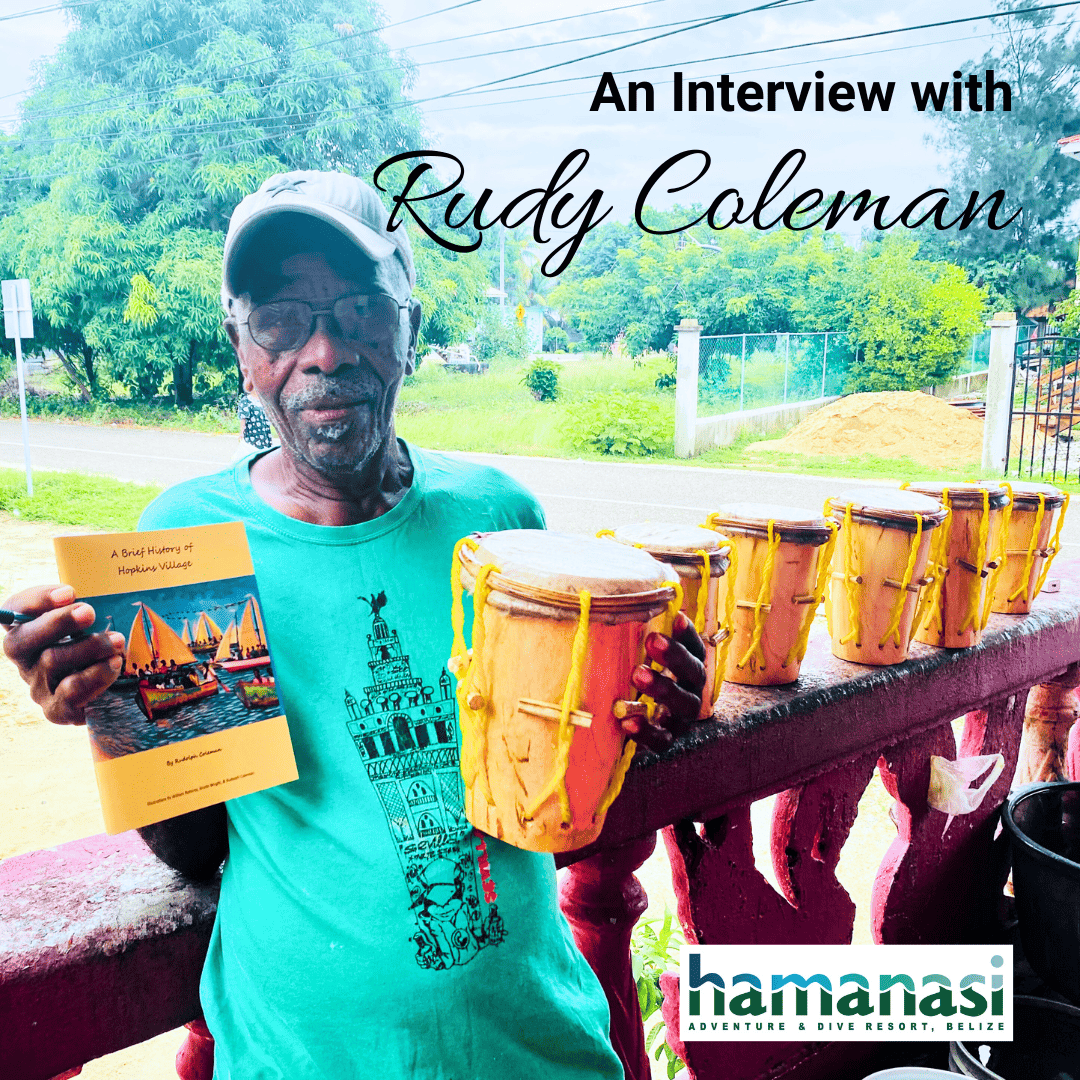

We met with the Hopkins Village elder, drummaker and historian, Rudy Coleman, to hear his personal reflections on the village he cherishes. Below is a transcription of most of the conversation.

Mr. Coleman with his book, “A Brief History of Hopkins Village”

What is your full name and age?

My name is Rudould Coleman. I was born on the 11 of May 1941. I am 82 years old.

How many children/grandchildren do you have?

Oh! Children, I have 9. I have 6 boys and 3 girls. I was counting my grandchildren and I have 25 grandkids, and I have about 15 great grandkids.

Where were you born?

I was born in the second Garifuna village before Hopkins, called Newtown. I was born in Newtown. We moved from Baja Mar, which was the first village, to the second village Newtown. So we are now in the third Garifuna Village of Hopkins.

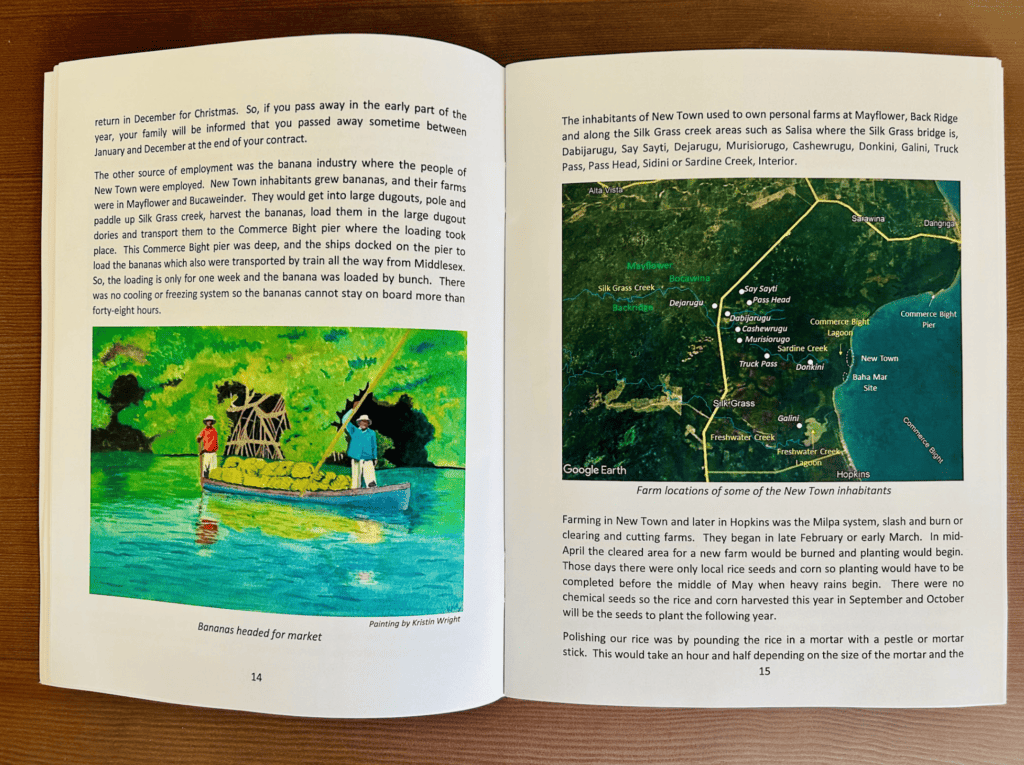

Map of the Garifuna areas from Mr. Coleman’s book.

When did you first come to Hopkins Village?

We come to this third village (Hopkins) in 1941 — in October of 1941. This last month was the 82nd year of when the people of Newtown began to migrate to Hopkins. After the hurricane of the 19th of September in 1941. The people had to move from Newtown to a much more desirable and safe place.

What was Hopkins like when you first moved here?

I was brought here when I was about a 4 month old child. My first word was here, my first step was here! So, growing up here was great! It was a settlement and the people were resilient people. Our people were closer to nature than now – it is different. Then, it (nature) was it – it was all we had and all we knew. In those days we were just like a beginners settlement from 1941 until the 70’s when it (Hopkins) got its first road.

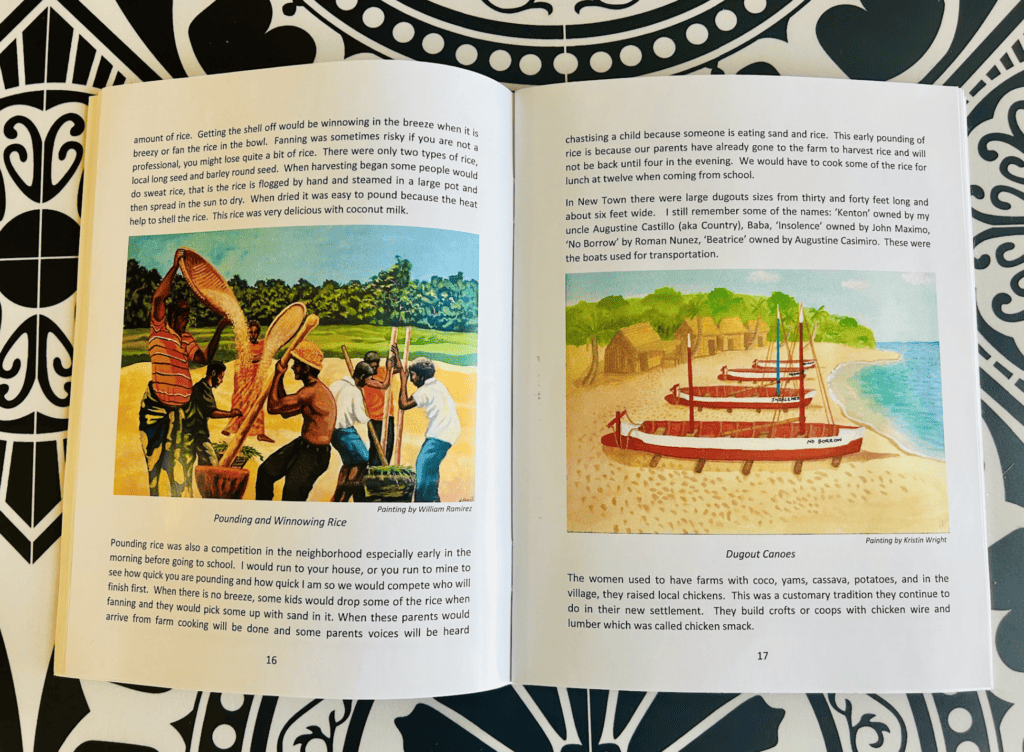

Book images of life in the the early days of Hopkins

When did the first roads come?

1970’s is when we got our first road. Before the roads, we had a traditional Garifuna way of living, where we used all we have. We used herbal medicine. Our way of life was depending on what we were. Our transportation for education was not like this. To get your child educated you had to go to Belize City to St John’s High School, which was the first school in this country. So if you wanted your child to go, they had to go to Belize City. If your parents were able to send you to college, you go. If they do not, you stay a ‘village boy’.

When did telephones and electricity arrive? What was the impact of these to village life?

Our first telephone system that was during the colonial days was the magneto type system. It was used a lot, especially to do our government business or when government officials arrived. The alcalde was in charge. They were the telephone operator. So, later in the 70’s we got the dial tone type telephone that was located at the community center by the police station. That was the second type of phone system, and it was well used. Then, it was moved to my sister’s house. My brother-in-law was in charge. He was the telephone operator and the registrar for birth and deaths. So all these little things was his job.

Later on we began to have the type of system we have now.

When & why did you decide to make drums? How is this an important part of your culture and life?

Mr. Coleman shows where he works on his drums.

Ok. When the Peace Corps began coming to Belize and they had to go to the villages to look at how the people live before they sent them to their stations. So they would come to Hopkins and we would have culture nights. I used to be the main person of the culture night to describe the dances, the drums, and things of the sort. So I would hire drums from the people. So it came to me that I had to own my own drums. So, well… I see drums, I know drums, because my father and grandfather had drums at home. So we would just play with the drums- not knowing that one day they would be the main money maker of Hopkins!

SO we would just go and play with drums. Because, you see, my grandfather used to play with drums. He used to be a drummer for what you would call the Garifuna Thanksgiving celebration, called the Dugu. He was a master drummer. My grandfather had 3 drums. I grew up seeing drums, so I thought I must be able to make drums. So, I went to the forest, because I know what drums are made of and the trees (mahogany) were not as scarce then. I cut down the tree, put the piece I want on my back and haul it to the lagoon side and put it on the dory and brought it to the village. Then, I begin to hollow and shape it and to make my own drums. Those two drums were perfect. After I finished it I used it and lent it out to people. And that was the end of those drums! I lent it to people and they never returned it. But it never bothered me. Since that time I’ve been making drums up to now. It was good that I learned to make drums. At that time my kids were going to high school, and I had to find extra money to maintain the family and send my kids to school.

Mr. Coleman checks on his drums.

Do you feel Drum making is important for culture and lifestyle?

Yes! It is important! It is our culture, it is us. I make drums without sitting around anybody, because it is you and you see. If it is in your genes, it comes down- it transcends.

To be a good drum maker you have to do it the best way you can. Do it to make yourself happy and that you make people happy. Everything you put in there is you. Don’t add anything foreign into it. Drum making is you. You can’t go down and sit with someone who is not from that culture… You learn to make it without anyone instructing you to do it. It’s just like the guys who play the drums. You don’t go to school to play those drums, it is just there. You don’t need to go to school to teach you how to move your hands. It is there, it is a print.

What other jobs did you do?

At that time I used to work on the jetty but it was seasonal , so when there was not a shipment at the jetty I didn’t have a job. I used to go to the farm. I used to have a serious farm where we planted thousands and thousands of peanuts. I also had a citrus farm. But after a while the citrus grew sour and it could not pay you. With only 10 acres it cannot pay you. The farming was a whole family job and if the crop cannot get you paid, then you have to quit it.

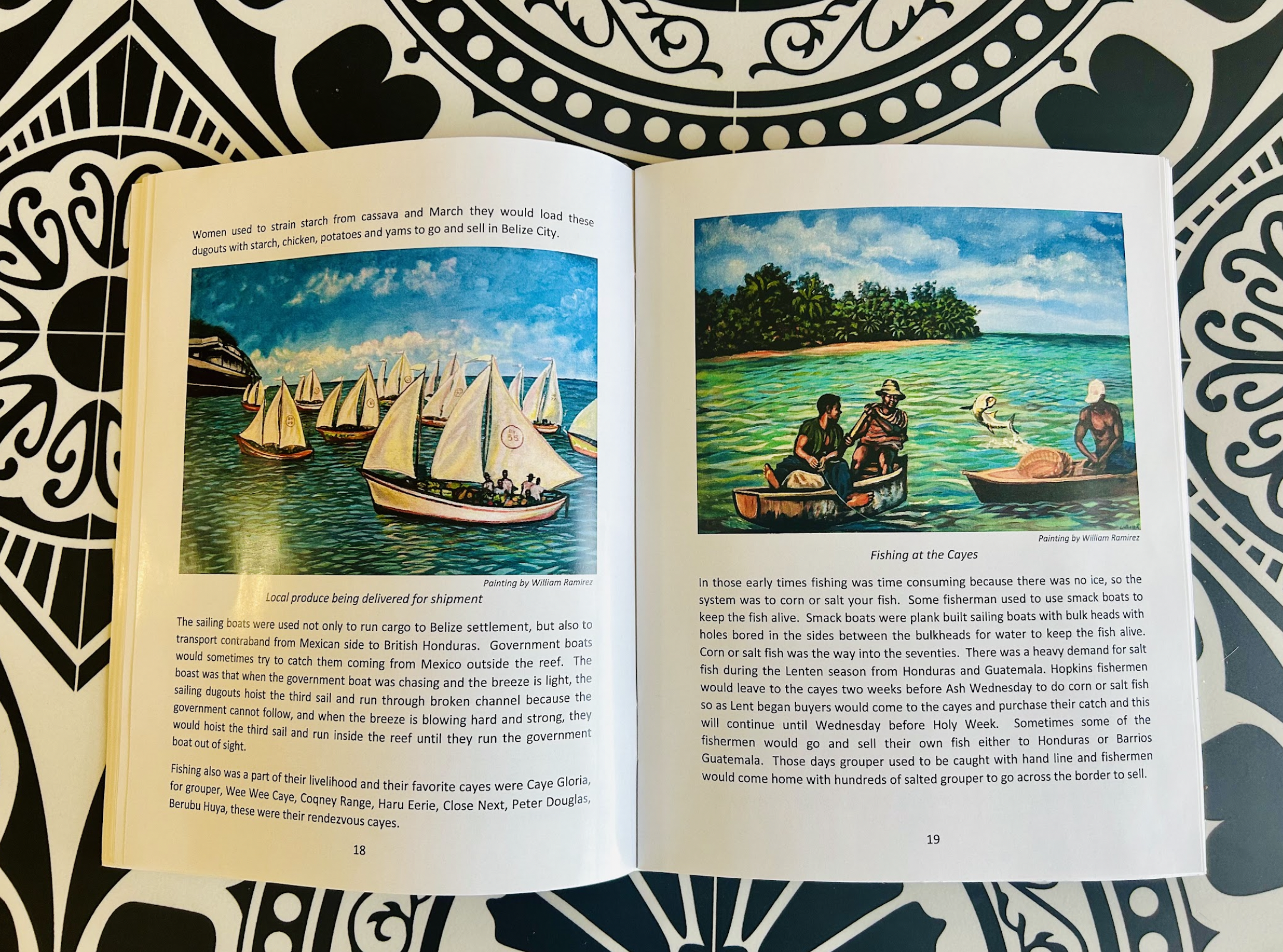

Images from Mr. Coleman’s book.

I also used to go fishing, long before my kids. My dad used to have two sailing boats. When I was 14 years old I manned my own boat. I used to sail by myself on a 20-foot sailing boat. My dad used to go to the bar by the lagoon. He loved fishing with cast nets. He would go to the bar and get a lot of fish and would get back at 2 o’clock am. He would call me out of bed, put all of the fish in my boat, then my mom and dad would help push me out and by 5 o’clock sharp I would dock in Dangriga. I would wait for the market to open. As the market opens, I am there with my father’s catch. Then I’m back home – by 9/9:30 I am already home.

Sailing was my delight. People would say if he is sailing I’ll get in that boat!

Now, Hopkins has people other than the Garinagu living there, Belizeans and foreigners. How has this impacted village life?

It has. Culturally and everything. Since that road is here, that road has changed this community. It has. Not for the worse, because it has to come. We cannot remain an isolated village culturally because of who we are. Yes we are, but because we are, people come to find out who you are. Because you are the maker. Hopkins is made not by those who are here now, it was made by those people who were culturally born and raised. People born in Hopkins were culturally raised. This is why Hopkins is now. Everyone comes to Garifuna Hopkins because it is a cultural village.

Tourism is relatively new to Hopkins beginning in the mid 1990s. How has that impacted village life, good and bad?

Like in anything, for things to happen there has to be both sides. There is not one side to anything. For everything that is good, there has to be bad, and for everything bad, there has to be good. It is a balance, it is a 50/50. For us to do good, there has to be bad. There has to be complaints — it is a part of development. There is no development if there are no disagreements. There has to be disagreement to agree to do what we need to do. Tourism has brought so much to this village no matter what people say.

Tourism is good, but it has to be balanced. I was happy to see that before tourism took root in this place there was consultation (about skyscrapers, village upkeep, development, and the environment).

Tourism is great. In those days, we did not see people coming in, it was only us. And there were no jobs, you had to go out and work in the citrus industry. Now there are jobs right in the village and people from all the way from Corozal and the Toledo district come here for jobs.

So it is great.

How are you connected with Hamanasi?

(Laugh) It’s a long history with Hamanasi, you know!

In the 80’s or 90’s when Charlie and Joan (the parents of one of Hamanasi’s founders) used to come and live at Sandy Beach, the first place opened for tourism in this area. They used to come and I used to walk with them to where Hamanasi now is to show them around and where the pegs were. And we had a very good relationship with Charlie and them. Then Dave and Dana (Hamanasi founders) came.

We have a very good relationship with those people. They are very wonderful people and they love this village.

What role do you serve as a village elder?

I am a justice of the peace, minister of the church, a drum maker, and sometimes an advisor. People come to me to ask what I think about. That’s a part of the elder’s job – for guidance. Mostly for historical questions. You have to be knowledgeable.

Where can one buy your book?

Mr. Coleman’s new book, “A Brief History of Hopkins Village” is for Sale in the Hamanasi Gift Shop

I have my book here (at his house on the Northside of the village). I tried to get it on Amazon, but we are still trying to find a way. You can get either a hard copy or digital version and we are still trying to find which way to go (for Amazon).

I have a few (books for sale) by Ella’s, Nice Cream, and my best seller is Ms. Emma at GariMaya Gift Shop!

What are your hopes and dreams for Hopkins and the Garinagu? What is your legacy?

My hopes and dreams for Hopkins is to one day have more education facilities. We have so many young kids here and we should really have a highschool here in this village so that the kids don’t have to travel to go to high school. So at present we are trying to get that whole block there by the library to have it surveyed and have it leased or purchased for this community.

The legacy I leave behind is these memories of this person talking to you. I don’t want to leave money, I don’t have money. What I have is me, my mind and myself. This is me and this is my wealth. My wealth is not in making drums. I make those drums to show that you are a Garifuna. It is a service I am giving. It is not making money. If I wanted to make money I would buy a lathe and make thousands of drums. Then where would I sell them? (He laughs) I do it this way-the way my grandfather started it. My grandfather never used to make money off of it. I am making little money to offer this service.

Rudy Coleman is a Hopkins Village elder, drum maker and historian. His book is available for purchase at the Hamanasi Gift Shop, as well as other businesses in the village such as GariMaya, Ella’s, and Nice Cream.